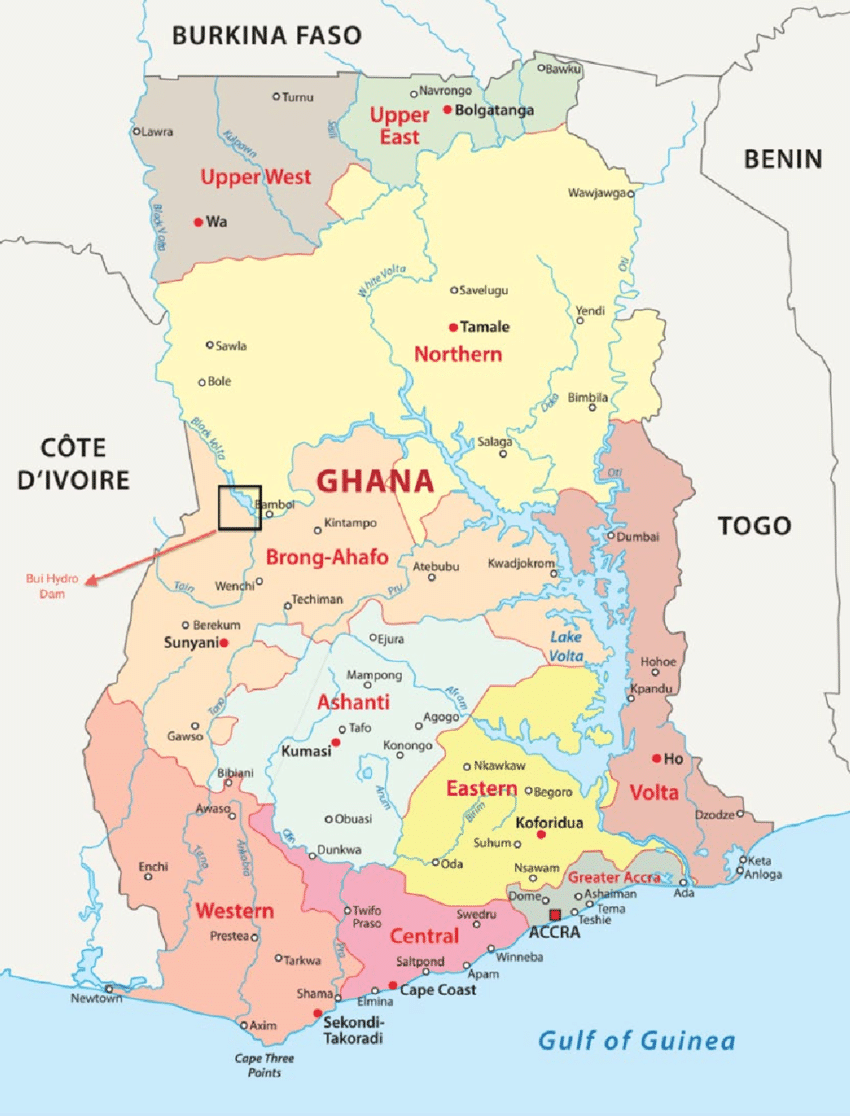

Bui (Bue) is a town that is composed of agro-fishery Nafaanra (Nafaana) and Deg-speaking people that form a subset of the larger Mo-Dega ethnic group in Ghana and Ivory Coast (Côte d ‘ Ivoire). The Deg language of the Mo/Dega belongs to the larger Gur language family and is a member of the Grushi (Gurunshi) subgroup (Anto 2010; Anto 2016). The Nafaanra language, however, belongs to the larger Senufo language spoken in Ghana, an outlier to the rest of the Senufo languages, which are spoken in Mali, Burkina Faso, and the Western part of Cote d’Ivoire (Garvin 2019:2). In Ghana, the Mo/Dega live in Nkoranza in the Nkoranza Municipal Assembly of the Bono East Region, Bui in the Tain District of the Bono Region, and the Bole in the Bole District of the Northern Region of Ghana. Bui is found on the northwest corner of Banda–Ahenkro, (Banda Samanku) in the Bono Region. This settlement is 400 yards to the southern bank of the River Kpaa (Black Volta).

Originally, Bui was Mo/Dega people who speak only Deg (Dega/Mo language) but their long historic contact with their dominant Nafaana-speaking Banna (Banda) neighbours led to their adoption of Nafaanra language (Apoh and Gavua 2016). Hence, Abrampah (2021:2) contends that this historic contact and acculturation underscores the reason why the people of Bui currently speak Nafaanra as a ‘lingua franca,’ and speak nominal Mo to maintain their identity. Currently, Bui, Mo/Dega are of Mo-Dega ethnicity, but they are on Banda stool land. This explains why the Chief of Banda attempted to have direct control of Bui lands, which the Bui people fiercely resisted. Though the Banda were aboriginal landowners, history affirms that Bui is migrants who have always had the usufruct right to Bui lands (Abrampah 2017).

The endonymic name Bue (anglicised as Bui) is from the Gblana dialect of the Gyaman and it means “they shall return” (Ameyaw 1969: 11). The name was about the Banda resettlement on the land after a long absence – when overthrown by the powerful Gyaman State. Abrampah (2021:2), however, argues that Bui is a corruption of the ethnic Kulango expression, booyi, which means “have gone away.” This, he argues, was about migrants who came to settle among the Bui people, but later left the area. Ameyaw (1969: 16) explains further: “The word “Bue” was used as a disparaging nickname by the Gyamans. The origin of the statement came about when Gyaman had the land by conquest from the people of Banda who later survived their defeat and re-occupied the land.”

The Bui town became very popular in the then Brong Ahafo (now Bono) Region when the Bui National Park was established in 1971. The Park is 1820 km² and is notable for its Hippopotamus population in the Black Volta. The endangered black and white colobus monkey and a variety of antelopes and birds are also present. Abrampah (2021) contends that Bui’s fame as one of the Mo/Dega towns was enhanced by a gorge, which had always been known as Bui gorge, which was developed to Ghana’s second major Hydroelectric Dam Project. Bui Dam is a roller-compacted concrete (RCC) gravity dam built on the Black Volta River (Kircherr et al., 2016). It is a multi-purpose dam with the key aims of electricity generation and water supply. Kircherr et al., (2016) and Abrampah (2021:1) contend that the plans for building the Bui Dam were first hatched by the British Colonial Administration in 1925, however, feasibility studies began in 1966 for the construction. General Ignatius Kutu Acheampong’s Supreme Military Council (SMC) regime made a bold attempt to build the Dam in 1978 (Kircherr et al., 2016). Unfortunately, the regime could not build it until President John Agyekum Kufuor’s New Patriotic Party (NPP) government under the Fourth Republic started building the Dam in 2007 with the Chinese Exim Bank (CEB) loan.

Origin and Migration

Two oral traditions explain the origin of the people of Bui. The first oral tradition of the Bui asserts that they were Mo/Dega migrants led by Jbroke from Wromalia to settle on the Bui land. They moved from their original habitat as a result of the slave-raiding activities of Samori and his bandits. The second oral tradition, however, asserts that Bui was part of the larger Mo/Dega people who migrated from the Sisaala (Tiwii) in the North following the dispute over the sharing of the dog’s head and legs as customarily demanded (Atta-Akosah, 2004; Hobbs, 1926). The conflict caused the Mo/Dega to move to Bole and the Black Volta enclaves. Upon their arrival in the area, the Mo/Dega pleaded with the Chief of Banda, Mgono Sielongo, to stay on the land. The Chief of Banda gave them the inhabited land lying immediately south of river Kpaa (Black Volta) and old Bui, which was named by the Hausa traders as Lua, meaning “water” (Ameyaw 1969:16). The place was on the main caravan route to the north and served a halt for the traders to and from the north across the river.

On their new settlement, Jbroke and his people secured a responsibility in ferrying wayfarers across the river Kpaa. The tolls they collected from wayfarers were sent to the Bandahene (Chief of Banda) who then held sway in the area. Out of the toll proceeds, a reasonable share was given to the head of the Mo/Dega at Bui. The hunters amongst them who hunted on the land also paid rights to the Bandahene.

Whilst on the Banda land, the Nkoranza attacked Banda at Gulubo. In this battle, Banda and their allies lost the field at Sabre and despairingly fled in every direction. Some of the people with the Banda Chief, Mgono Sahkyame sought refuge at Akomadan; another group went and settled at the southern bank of the river Kpaa which place was later named Bue, Gblana dialect of the Gyaman, meaning “they shall return” (Ameyaw 1969:11). This was about the Banda resettlement on the land after a long absence – when overthrown by the Gyaman.

Ameyaw (1969:16) recorded that Jbroke ruled the Bui people for a long time before he died, but because he had no male heir to succeed him, Wuro Kwabena, the head of the family was selected to succeed him based on matrilineal lines of succession. When Wuro Kwabena took over from Jbroke, his junior brother, Sie Daglo, who lived with his kinsmen on the northern bank of the river moved to join them. It was during the reign of Wuro Kwabena that Samori and his slave-raiding bandits reached Bui to terrorise the area. Samori’s son, Issa was made to be stationed at Bui with his army to engage in slave-raiding in the area until the arrival of the Europeans in the area in 1896 caused him to flee.

After Wuro Kwabena’s death, Sie Yaw, his nephew and the son of Akosua Hanyapo succeeded him. Sie Yaw tenure as the Chief of Bui was uneventful. When he died, Gandaw Kofi, son of Abena Kuma succeeded him and reigned peacefully for a long time. Upon his death, Dabla Kojowo, son of Akua Bi succeeded his uncle and reigned for many years. When he also died, Sie Dabla, son of Adwoa Dabane succeeded him.

Reference

Abrampah, David Akwasi Mensah. “Haggling over graves and shrines: The Intersection

of Archaeology, the Community, and Dam Authorities at the Bui Dam area in Ghana.”

Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage (2021): 1-16.

___. “Strangers on their own Land: Examining Community Identity and Social Memory of

Relocated Communities in the Area of the Bui Dam in West-Central Ghana.” Human

Organization 76 no. 4 (2017): 291–303.

Ameyaw, Kwabena. “Oral Tradition of Bue” in: Kwabena Ameyaw (ed.), Oral Traditions

from Brong-Ahafo, Ghana. (Accra: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana,

1969).

Anto, Sylvester Kwabena. “A Comparative Study of the Nominal Group Structure of

English and Mo/Deg.” (MPhil Thesis, University of Ghana, 2010).

___.“Syntactic Survey of Determiners in Mo/Deg Language.” Advances in Language and

Literary Studies 5, no. 4 (2014): 125-136.

Apoh, Wazi, and Gavua, Kodzo. “‘We Will Not Relocate until Our Ancestors and Shrines

Come with Us’: Heritage and Conflict Management in the Bui Dam Project Area,

Ghana,” in, Peter R. Schmidt and Innocent Pikirayi (eds.), Community Archaeology

and Heritage in Africa: Decolonizing Practice. (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Garvin, Karee. “Progressive Fronting in Nafaanra: A Case Study of Altruistic Movement.”

(2019).

Kirchherr, Julian, Tim Disselhoff, and Katrina Charles. “Safeguards, Financing, and

Employment in Chinese infrastructure projects in Africa: the case of Ghana’s Bui

Dam.” Waterlines (2016): 37-58.

PRAAD, Kumasi, ADM/ARG.I/2/2I/1, Notes on History of Mo, H.J. Hobbs, Acting

Provisional Commissioner.