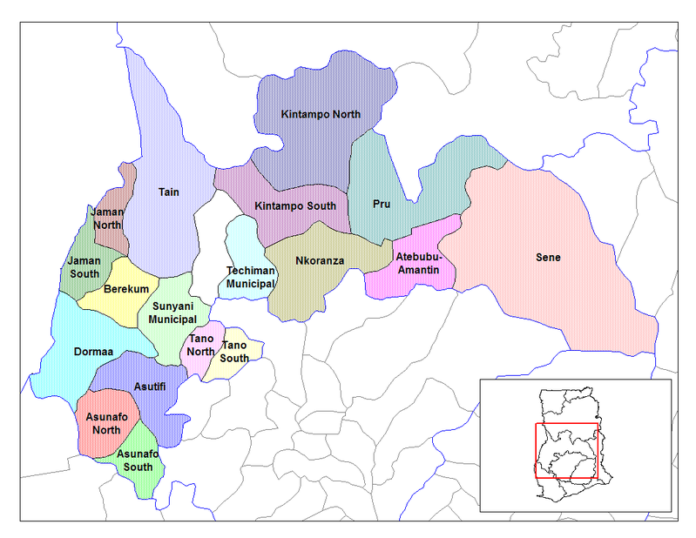

The Yeji are an amalgamation of agro-fishery Guan Chumuru-speaking people found in the Pru East District of the Bono East Region of Ghana. Yeji, which is the administrative capital of the Pru East District and the seat of the Yeji State, is bordered to the north by Atebubu and adjacent to River Volta. It is on the Ejura-Tamale road at the place where the ferry crosses Volta Lake. It is connected to Makango on the northern bank of the Volta Lake from where Salaga and other parts of Northern Ghana can be reached. Yeji, according to Benneh and Dickson (1988:136) exemplifies one of the towns which has developed at a point where a major trade route crossed a river in Ghana. The town is one of the few major ferry sites in Ghana.

Despite being Guan group, the Yeji are an amalgamation of various Guan and Akan groups that congregated in the area before other ethnic groups such as Nchumuru, Gonja, Nawuri, Konkomba, Hausa, Kotokoli, Ewe, Yoruba-Lagosians, Fulani, and others from southern coastal Fante towns who came recently to the area for fishing activities. Thus, Abrampah (2014:126) notes that: “the strategic location of the town has turned it into the important market centre and major transport hub” by serving “as the transit point for goods and people travelling between the north and south of Ghana.” The Fante presence in Yeji has turned the town into one of the most important inland fishing economies in the country. The Fante fishing groups founded the village of Fante-Akura in Yeji.

The Yeji people call themselves Nchumbulu (sing. Chumuru) or Yeji, their language Nchumbulu (Chumuru) and their land as Yeji. Two known theories underpin the origin of Yeji, but there has developed a new revisionist one. In the first theory about the meaning of the ethnonymic-exonym, Yeji, Braimah (1939:54) contended that the Yeji emanated from Ngbanyito word yaw-ji , meaning “trade casualty” or “they confiscate”, and the Akan twi word yɛ-gye (ye gye), meaning “they confiscate.” is said to originate from both Ngbanyito (Gonja) and Akan-Twi languages. Braimah (1939:54) recorded that Yeji is a vulgarisation of the Ngbanyito (Gonja) phrase, yaw ji Akan Twi phrase, yɛ gye (ye ji). He explains that the Guan-speaking people earned the exonym from both the Ngbanya (Gonja) and the Akan-Asante groups because, during the period when Salaga market was at its apogee, the traders from Ashanti who travels to Salaga Market on their return had their merchandise confiscated and are either killed or kidnapped and sold into slavery. This act of violent seizing of merchandise (robbery), and kidnapping on that space where the Yeji town was built earned the settlements name, Yawji/yɛgye, now Yeji.

In the second theory of Yeji, Fordjor (1966:18) explains that upon arriving on the present-day Yeji enclaves moved to live close to the Kuli, but after experiencing series of kidnapping and selling of their people into slavery by the Kuli moved back to the Konkoma with a complaint, bafe na bagyi “they sell us and make use of the money”. Fordjor explained that bagyi or baji means “make use of the money”, “eat”, or “they eat”, and it is baji that was vulgarised to Yeji. Recently, Anane-Agyei (2012) has introduced a third or new theory claiming that Yeji emanated from the Chumuru word Aniyeji, meaning “let us go and eat”, which later vulgarised toYeji. He explains that whilst Kachempo were living at Kachempo, two great hunters called Yao Kisikwa [Gyima Panin] and Kwame Banka undertook an expedition to search for suitable drinking water. After several attempts, they finally discovered the Titabɔr/Adrɛ (River Volta) and reported it to the group at Gyakaboye. According to Anane-Agyei (2012) when the hunters ran to their chief to report their pleasant discovery, they exclaimed mirthfully in their native language Aniyeji, meaning “Let us go and eat”.

Linguistically, Nchumbulu (Chumuru), the language of the Yeji is a variant or dialect of the original Kyoŋboroŋ-nɔ (Chumburung) language of the Nchumuru. Nchumbulu (Chumuru) belongs to the North-Guan branch of the larger Guan languages that forms part of the Niger-Congo language phylum (Simons and Fennig 2018; Hansford 1989, 1990; Hansford 1990:29; Snider 1990, 1989a; Dolphyne and Dakubu 1988:79). In the North-Guan group, Nchumbulu (Chumuru) is associated with its parent language Kyoŋboroŋ-nɔ (Chumburung) as well as Dompo (Dompofie), Kɛnyɛn (Dwang), Kaakye (Krachi), Gikyode (Gichode/Atwode), Ngbanya/Ngbanyito (Gonja), Kplang (Kprang), Nawuri, Nkonya, Foodo and Ginyanga. Per the Snider’s (1989) subdivision of the North-Guan group into Oti-Mountain and Oti-River languages, and assigns Nchumbulu (Chumuru) is classified together with its parent language Kyoŋboroŋ-nɔ (Chumburung) and Kaakye (Krachi) as members of the Oti-River sub-branch of the North Guan languages. Dolphyne and Dakubu (1988:77) note that there is Nchumburu (Chumuru) shares a considerable amount of mutual intelligibility with its parent language Kyoŋboroŋ-nɔ (Chumburung) as well as Kplang (Kprang), Kɛnyɛn (Dwang), and Kaakye (Krachi), but considerably less intelligibility between these forms and Ngbanya/Ngbanyito (Gonja) or Gikyode (Gichode/Atwode).

Yeji is a patrilineal-patrilocal type of society, a man lives in a kabuno “compound” with his wives, his unmarried sons and daughters, widowed sisters, aged relatives, and sometimes unmarried sisters and brothers, maybe up to 20 people. A man inherits farms, livestock, gun, children, and property from his father, junior or senior brother. A woman, may, however, inherits clothing and kitchen utensils from her mother or junior or senior sister. A deceased man’s junior or senior brother used to be duty-bounded to marry his widow and take care of his children. In terms of political authority, the Yeji State has a paramount chief at the top of its chieftaincy structure. He rules with sub-divisional chiefs who are selected by their own community’s royal lineages. Succession to the Yeji paramount stool is patrilineal, hence sons of male and female royals of the chief’s family are eligible to ascend the stool. Sons of a chief’s daughter are also eligible. In Yeji State, Cherepo constitute the Kyidom division, Kojo Bofour (Yajawure) is the Adonteng division, Kpakpa (Kpakpawure) is the Kronti division, Kapoase is the Ninfa division, Kadue (Kaduewure) is the Benkum division, Ankobeahene is the Asasewure, Kacha (Kachawure) constitutes the Bamu. Nana The queen mother position was first introduced in Yeji under Nana Kwaku Yamba, the 16th occupant of the Yeji stool with Nana Abena Kanyiwechor as the first queen mother of the state (Anane-Agyei 2012).

The Yeji are very religious, thus the three religions of Christianity, Islam, and African Traditional Spiritualties are found in their territory. In the past, most of them were Traditional African Spiritualties practitioners. The Yeji believe in the existence of a Supreme Being called Wuruboare “God the creator” who is connected with the concepts of “goodness and all that is good, and with the cooling fertilising blessing of boare “rain” (Lumsden 1977). Wuruboare is holy, sacred and has no shrine, though he plays an important role in the life of every individual. He holds the “destiny” of individuals before they are born. Below the Wuruboare are the deities with their shrine and ancestral spirits. The major deities in Yeji are Krachi Dente, Kyenkyemba, Gwesare, and Agyaware. The Yeji worships the renowned Krachi Dente deity, who is known for protecting the Guan groups in their warfare. The common worship of the Dente oracle by the Guan ethnic cluster in the Oti, Bono East and Northern Regions of Ghana is an indication that these Guan ethnic groups have a common history of origin to Larteh in Akuapem mountain, the area from which the Dente oracle migrated from to settle at Krachi.

The powerful indigenous deity of the people of Yeji is Agyaware which has the asasewura “landowner” (who doubles as Ankobeahene) of Yeji as the ritual custodian. The asasewura has been the caretaker of all the peoples’ land rights from Larteh to their present home. There is Kyenchemba (Chenchema) deity whose shrine is in Yeji town and is the deity of the Omanhene. Yeji has a minor deity called Taka “take and swear”, which they swore officially at the chief’s court. This deity was said to have been discovered by a Yeji man called Kwesi Tentrentu whilst on a canoe journey to visit the Queen-mother of Kafaba. Whilst on the river, his canoe was suddenly stopped by a mysterious power thus when he made it there and returned, he told the Yeji elders who delegated Krontihene Kojo Lagyawo to investigate the mystery. Lagyawo found the place to be a home of a deity, so he brought his people to the area to carry the deity back to Yeji and named it Taka, meaning “take and swear.” The supreme deity of the Kadue is Lamba.

The people of Yeji celebrates Kajuji “Yam eating” festival on every last Fofie “sacred Friday” of November (Acquah and Owusu-Ansah 2020:34), thus when yam is harvested chiefs as the custodians of the land are the last group of people to eat new yam in the Yeji state. At this festival the political authorities and religious leaders ate new yams, marking an important transition in the agricultural calendar. Before the chiefs could eat the new yam, they first offer it to the deities, particularly Kurumbuse deity, and ancestors for giving them bumper harvest and ask for protection, prosperity, rains and a bumper harvest in the next planting year. The act of eating new yam by chiefs and elders of Yeji state is known as awura aji iju “chiefs eating yam.” At the heart of the Yeji Kajuji festival nowadays is the performance of the Abele music, which is the genre of the youths of Yeji (Acquah and Owusu-Ansah 2020:3434).In the past, awura aji iju is preceded by three events: the Chanchamba rituals which place a ban on drumming and noise-making in Yeji, the carrying of graveyard sand of prominent individuals within the communities in Yeji known in Chumuru as ɛse fo kesɔrɔ, and the calling the ancestors to ascertain the cause of their death known in Chumuru as kanora fo kɔfoɛ. The Kajuji festival was first celebrated during the tenure of Nana Akesepra as the Chief of Yeji.

Agriculture comprising farming and fishing is the main economic activity in Yeji. The farmers cultivate yams, cassava, beans, groundnut, corn (maize), and guinea-corn (Lumsden 1971:29). The Yeji sells the yam tubers to non-Yeji buyers at the Yeji Market days, and they also sell this staple in the major markets of Accra and Kumasi. Women cultivate pepper, garden eggs, okra, and groundnuts among their husbands’ yam mounds, and carry produce home for domestic consumption, whilst the surplus is sold. The Yeji also keeps ungulates (goats, sheep, and cattle), pigs, and chickens for domestic and commercial purposes. In addition, and most importantly, fisheries-related economic activities have been the mainstay of communities around the Yeji side of the Volta Lake as the inhabitants directly or indirectly depend on fisheries as their means of livelihood. The fishery economy supports children who are actively involved in the industry as school dropouts whilst some are combining both (Asante 2018).

The Volta Lake with ferry service and thriving market further positions Yeji as the largest inland supplier of smoked/salted fish, cattle and other food crops in the district. As the only means of transport on the lake, transport boats collect the weekly produce of processed fish from villages along the lake in Stratum VII and transport them and their owners (who are either the processors or long-distance fish traders travelling to the fishing villages to buy processed fish) to Yeji on market days. Although fish is marketed at a few other markets in the lake area, the Yeji Market is preferred by most operators due to better prices and a guaranteed market. N’jie and Jones (1996:5) explain how the Yeji fishing marketing is operated, thus: Fish marketing in Yeji is based mainly on the Ntumu system. The Ntumus are fish traders (generally young and middle-aged women) who operate stalls they rent or construct on their own. Incoming processors or traders agree with the Ntumu woman on the price of the fish. The Ntumu then bargains with long-distance fish traders coming from various distribution centres in the metropolitan areas of Kumasi, Accra and other places on fish distribution centres for Yeji). When the fish is sold the Ntumu receives a previously agreed commission from the owner of the fish and at times also from the trader. Long-distance traders load fish on transport vehicles specialised in the trade for specified charges depending on the size of baskets. Fish departing from Yeji also pay levies collected by the local authorities.” The Yeji market is currently the second-largest market centre in the Bono East of Ghana after Techiman.

Origin and Migration

The Yeji Nchumuru group were originally a combination of six autonomous clans or division including Kachempo, Kpakpase, Yaja, Kadue, Cherepo, and Konkoma. However, the Konkom who were early immigrants of Akan Denkyira stock has cut off their umbilical cord to the Yeji confederacy to form an independent state of their own (Kumah 1966). The remaining five divisions that still forms the Yeji State has three Guan groups: Cherepo, Kpekpa (Kpakpa), and Kachempo, whilst Yaja and Kadue are of mixed Akan-Guan immigrants from Effiduase and mixed Akan-Kafaba-Gonja from Takyiman and Kumfia respectively. The oral tradition of the ruling Kachampo division asserts that their ancestors came to their recent place of residence with the Kpakpa and Cherepo from the Larte and Apirade respectively (Kumah 1966).

The Kachempo (Yeji) contends that they evacuated from their settlement in Larteh to seek a suitable place to settle because of the internecine conflicts on the Akuapem Mountain as well as the suppression and maltreatments of the Guan people by the Danes and their Akwamu collaborators. The Danish administration via the Akwamu used chicanery of job opportunity to prevail on the hilly Guans to be the carriers of palm nuts to their ships, and then they make volte-face to sell them into slavery. As a result, their ancient deities, Krachi Denteh and Chenchemba rebelled and led them through their journey with the Nkonya and Krachi. The Kachempo (Yeji) were led from Larteh by Nana Agyeman [Gyima] Panin to cross River Volta together with the Nkonya and Krachi. After crossing the Volta, the Nkonya and Krachi proceeded to settle at their present places, but the Kachempo (Yeji) pushed forward and settled first at Kachempo where they met the Wiase in the present-day Sene West District, who were the only ethnic group they came across in the neighbourhood.

After settling at Kachempo for many years, severe drought forced them to evacuate from the area to settle at Gyakaboye. Whilst living in this settlement, two great hunters called Yao Kisikwa [Agyeman Panin] and Kwame Banka undertook an expedition to search for suitable drinking water. After several attempts, they finally discovered the Titabɔr/Adrɛ (River Volta) and reported it to the group at Gyakaboye. Anane-Agyei (2012) explains that when the hunters ran to their chief to report their pleasant discovery, they exclaimed mirthfully in their native language Aniyeji, meaning “Let us go and eat”, and the term Aniyeji was vulgarised toYeji. The Kachempo left Gyakaboye to settle permanently at the new place, Yeji. Amongst the Kachempo group that came to settle at Yeji from Larteh, the Yaja branch were Aduana emigrants from Larteh who moved to Effiduase in Ashanti Region before coming to Yeji. The Kpekpa (Kpakpa) were also immigrants from Larteh, who moved to settle first at Agogo under their leader Nana Kojo Lajao before finally settling at Kachempo/Yeji (Kumah 1966:3; Fordjor 1966:38).

On Kadue group who are a division of their own were, Kumah (1966) averred that they are a mixture of ethnic groups that migrated from Takyiman as Kumfi Yaw (Kumfia) group and the Kafaba Gonja, but Fordjor (1966:30) disagreed and stated that the Krontihene of Kadue was the one who belonged to Kumfi Yao (Kumfia) group which used to elect the chief but lost their stool as a result of indebtedness. Fodjor, however, posited that the Kadue emigrated from Larteh and they were led by Nana Kamapong to settle first at Kojo Bofour. From Kojo Bofour, three notable hunters: Arabraka, Kwame Takyi, and Nyantiri discovered Kadue and pitched camp there. Later, the rest of the people moved to settle there, but when Nana Kamapong died at Kadue others moved out to found hamlets such as Kupua, Ajantriwa and Langase (Fordjor 1966:26). enclave and led the group move. The movement from Kojo Bofour to the new place brought the name Kadue. At Kojo Bofour, when the people are going for hunting expedition at what is now Kadue, they say in Nchumuru language: kadi wa ye, meaning “we are going to eat and sleep” (Fordjor 1966:26). The expression kadi wa ye, was shortened to the toponym, Kadue.

According to Kumah (1966:3), the Kyerepong (Cherepo) Division of Yeji was initially part of the Konkoma Division of the Yeji Traditional Area but is now a separate division under the same traditional area. The Kyerepong (Cherepo) have two traditions of origins, whilst one claims they are autochthones in the area, the other contends that they were aboriginal Guan who migrated from Larteh to the area. Fordjor (1966:43) posited that the Kyerepong (Cherepo) ancestors sprang from a rock in the River Pro (Pru), which is now a revered shrine. Hence, the name Kyerepong is said to be derived from Kyrupo, meaning “from water.” Another oral tradition collected by Kumah (1966) and Fordjor (1966) averred that the ancestors of the Kyerepong (Cherepo) emigrated from the Kyerepong-speaking town of Apirade on Akuapem Mountains to settle at their present area amongst the Yeji. The Kyerepong (Cherepo) avers that before they came to settle Apirade, they were residents of a settlement called Kpombo Takpon, which is described to be between the Savanna land (Kumah 1966:4; Fordjor 1966:47). Their neighbours were the warlike Konkomba group that disturbed their peace, thus their chief and leader, Nana Kpambo led them to the south to settle at Accra Plains. Skirmishes with the Ga, Akyem and the Kankanbrofo “the Portuguese/the Dutch” forced them to evacuate from the area with their fellow Kyerepong group to settle at Apirade on Akuapem Mountains (Kumah 1966:4; Fordjor 1966:47). After staying for some time, internecine conflicts in the Akuapem enclave made their leader, Nana Kpambo move them further north by travelling on the right bank of River Volta crossing rivers Affram, Obosom and Seni to finally settle at Cumpu, the then town of the Nchumuru.

The Cherepo reached Cumpu at the time when the Nchumuru was ruled by a despotic king, Nana Kentenku. The Cherepo assisted the Kɛbekya (Bassa) from Wassa, the Wiase (Ɛwɔase) and Ashanti to fight and defeat the Nchumuru who fled across the Volta to various towns such as Nkelelo, Nanjiro, Wiae, Papatia, Bejamso and others (Kumah 1966:4). After the defeat of the Nchumuru, the Cherepo moved northwards to occupy the northern corner of the Volta lands by defeating small bands of people of mixed ethnicities. They finally established their town called Kyerepong on the northwestern corner of the Volta River and later became part of Yeji State. Because the inhabitants could not mention their toponymic name Kyerepong, they corrupted it to Kyerepo (Cherepo). They founded Konkonse and Ayimaye communities. Their deities are Krachi Dente, Nana Pru (deity of River Pru), and Kigyinonelɛɛ (Kumah 1966:5). The Kigyinnonelɛɛ oracle is the indigenous and the Cherepo national oracle which they brought from Apirade on Akuapem Mountains, thus the Chief of Cherepo serves as its Priest. The stool name of the Cherepo is Nana Brofo, which is a black stool.

The Kachampo and its divisions that makes Yeji became adept at ferrying people across the river and keeping the proceeds. Whilst their communities were developing, Ndewura Jakpa, the Mande horse-riding warrior founder of the Ngbanya (Gonja) State passed through their lands and met Nana Eburo, Yeji elder who gave him fish and meat. Jakpa in return, gave him a young man to be his assistant. Nana Eburo assigned the young with the task of rearing fowls and named him Krebewura, which became the official title of the chief of Kuwuli (Makango, the northern landing of the Yeji ferry). In 1744, the Asante in their war of conquest invaded the Volta Basin and the Northern territories and defeated the ethnic groups occupying these lands. As a result of this defeat, Yeji fell under the Asante suzerainty and started paying tributes in form of fish, human beings, money, mats, and others to the Asantehene at Manhyia in Kumasi. Juaben State’s Chief, Nana Akrasi and later Ate was delegated by the Asantehene to oversee the Volta Basin, autochthonous groups. One, the day the Asantehene through his representative Nana Akrasi demanded from Yejihene Nana Kwesi Gyima the tail of a fresh hippopotamus and the Yejihene’s father, Nana Kyikyinda supplied it promptly. As a result of this act, Nana Kyikyinda was enstooled as Kojo Bofourhene “Friday-born Chief of all Hunters”.

Reference

Abrampah, David Akwasi Mensah. “Anthropological Examination of Yeji Salt Trade

and its Linguistic Repertoire”, in, James Anquandah and Benjamin Kankpeyeng

(eds.), Current Perspectives in the Archaeology of Ghana. (Accra: Sub-Saharan

Publishers, 2014).

Acquah, Emmanuel Obed, and Justice Owusu-Ansah. “Abele Indigenous Musical Genre

in the Context of Yeji Kajoji Festival.” African Journal of Culture, History, Religion

and Traditions vol. 4, no. 1 (2020): 29-40.

Anane-Agyei, Nana Agyei-Kodie. Ghana’s Brong-Ahafo Region: Story of an African

Society in the Heart of the World. (Accra, Ghana: Abibrem Communications, 2012).

Asante, Vida Rose. “Children’s Perspectives on Work and Migration in Yeji, Ghana.” (M.

- Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, 2018).

Braimah, J. A. Gonja: The Struggle for Power: A Brief History of the Gonja People.

(Author: Salaga, 1939).

Dickson, Kwamena B., and Benneh, George. A New Geography of Ghana. (London:

Longman Group, 1988).

Dolphyne, Florence Abena and Dakubu, Mary Esther Kropp. “The Volta-Camoé

Languages”, in, Mary Esther Kropp Dakubu (ed.), The Languages of Ghana.

(London/New York: Kegan Paul International for the International African Institute/

Methuen, 1988),

Fordjor, P. K. Prang-Yeji Traditions. (Legon, Accra: Institute of African Studies,

University of Ghana, 1966):

Hansford, Gillian F (ed). Kyo̱ŋbo̱ro̱ŋ-nɔ – Bo̱rɔfo̱-rɔ, Bo̱rɔfo̱-rɔ – Kyo̱ŋbo̱ro̱ŋ-nɔ

Ase̱ŋkpare̱gyi Ao̱re̱ Dabe̱ (Chumburung – English, English – Chumburung Dictionary:

A Bilingual Dictionary for the Chumburung Language of Northern and Volta Region.

(Accra: Ghana Institute of Linguistics, Literacy and Bible Translation, 1989).

___. “Permeable Ethnic Boundaries-The Case for Language as Unifying Factor for the

Chumburung of Ghana.” (MA thesis, 1990).

Hansford, Keir Lewis. “A Grammar of Chumburung: A Structure-Function Hierarchical

Description of the Syntax of a Ghanaian Language.” (PhD. Dissertation, Department

of Phonetics and Linguistics School of Oriental and African Studies-SOAS, University

of London, 1990).

Kumah, J. E. K. “Yeji and Cherepo Traditions”, in, J. E. K. Kumah, (ed.), Krachi

Traditions. (Legon, Accra: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, 1966):

IAS. Acc. No. JEK/16.

Lumsden, D. Paul. “Schooling, Employment, and Lake Volta: The Nchumuru Case in

Ghana.” Manpower and Unemployment Research in Africa, vol. 4, no. 2 (1971): 26-45.

N’jie, Momodou, and Jones, Ritchie P. “People’s Participation and Sustainability Aspects

in the Fisheries Project of Yeji, Ghana.” Programme for the Integrated Development

of Artisanal Fisheries in West Africa, Cotonou, Benin, 4Op., IDAFIWP/95 (1996).

Simons, Gary F., and Fennig, Charles D. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 21st

Edition. (Dallas, Texas: SIL International, 2018): http://www.ethnologue.com/

Snider, Keith L. “The Vowels of Proto-Guang.” Journal of West African Languages 19

(1989): 29-50.