Introduction

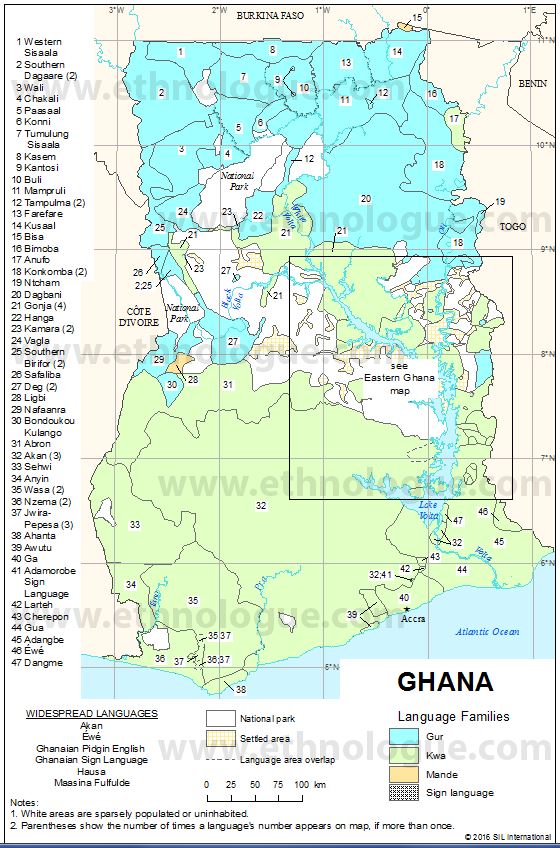

The Adele (Bédéré/Bidirɛ/Bidire) are agriculturalist, Guan, and Giderɛ/Sɛdɛrɛ-speaking people found in the north of the Mountainous Oti Region, east of Dambai ferry and adjoining the Togo border. In Ghana, the Adele is found in Jasikan, Nkwanta South, and Nkwanta North Districts of the Oti Region. They are centered around the towns of Nkwanta, Dadiasi, and Dutukpene, whilst in Togo, they are found in the Sotouboua Prefecture of the Centrale Region centred around the towns of Assouma Kedeme and Tiefouma. The western part of Adele land separates to some extent the Cala (Kabye, Tem and Kasuntu) from the Dulo (or Ntrugbo/Nyagbo).

The Adele call themselves Bidirɛ/Bédéré (Bidire) and their language as Giderɛ (Gidere) or Sɛdɛrɛ, northeast of Krachi and east Nchumburu (Kropp & Ford 1988:120; Rongier 1998; Kanchoa 2014). The Giderɛ/Sɛdɛrɛ is a member of the Ghana-Togo Mountain languages (GTM), formerly called Togorestsprachen (Togo Remnant Languages) or Central Togo languages. They are composed of fourteen languages including Animere, Kebu, Sɛlɛɛ (Santrokofi), Tuwuli, Igo, Ikposo, Siwu (Lolobi/Akpafu), Likpe (Sɛkpɛle), Tùtrùgbù (Nyagbo), Lelemi, and Avatime (Siya) amongst others that are spoken on the mountains of Ghana-Togo borderland. These languages form a subset of the Kwa subgroup of the Volta-Comoe branch of the Niger-Congo language family. Kanchoa (2014) observes that Giderɛ/Sɛdɛrɛ is a language with a complex morphology which presents morphologically the same characteristics as those generally observed in the Gur languages. Giderɛ/Sɛdɛrɛ are of two forms: The Lower Giderɛ/Sɛdɛrɛ (Adele) spoken mainly in Ghana and the Upper Giderɛ (Adele), a Volta-mono language spoken in Togo.

Adele are agriculturalist who cultivates yams, cassava, plantain, beans, cocoyam, and rice. They also hunt for antelope, deer, bush cow, and bushpig. The Adele live in nucleated villages of small compounds. Most houses are rectangular and thatched, with one main courtyard and the kitchen in a separate room. For the early Germans, Adele was the mountainous region of Middle Togo where the Gold Wolf settled in 1888- the post of Bismarckburg (Cornevin 1969:50). It was an important place for rubber production and economic importance.

In their religious cosmology, the Adele Supreme Being or High God is called Wurubare. They call on Wurubare whenever they are in distress. The high god, first on. Kiliji is spoken only by women, and only in a ritual context. Brindle et al. (2015) and Ntewusu et al. (2020) contend that the Adele are amongst the other Guan group such as the Nawuri (Balai), Atwode (Achode) and a few others are the ones that practice Okule or [oʤo]) Alija [oko aliʤa] is collectively known as Oko cult. In Okule’s spiritual system, women speak a secret ritual language known as Kiliji [kiliʤi].

Origin and Migration

The origin of the Adele (Bédéré/Bidirɛ) has two theories based on Ghana and Togo origins. Cornevin (1969:45) recorded that based on oral tradition in the British Togoland (now part of Oti Region), the Adele claims to have originally inhabited on the land close to the Osu lagoon in Accra. This probably makes them part of the aboriginal Les who was on the land before the Ga people emerged on the Accra plains and the coast. It is said that they lived on the Lagoon close to Osu until the invasion of Accra by the Akan group (Akwamu or Akyem or Juaben) forced them to flee the area. This makes them one of the several groups fleeing north and east from the wars west of the Volta in the middle of the 18th century.

Adele asserts that when they were defeated their leader Fireko-Jou, took in a magic drink that allows him to fly. Cornevin (1969:45) narrates: “According to their legend, on the evening of their defeat, their leader Fireko-Jou drank a magical potion which allows him to fly away. Hence, he flew over several mountainous regions and made his choice on a wild country that separates the Anié basin from that of Oti. He told his people that a favourable place has been found and the survivors of Osou joined him on foot.” On their journey to their present territory, especially to the east, they met an aboriginal group already on the land who worked iron. They absorbed the aboriginals and took their language.

This version of coastal origin is disputed by scholars such as Westermann who supports the historical rendition of Debrunner (1968) and Cornevin (1969) versions from Togo. In this oral tradition, Debrunner (1969:553) recorded that the western Adele argues that their ancestors came down from heaven by climbing down on a magical chain that disappeared immediately after the last person came down. The people were led down by ancestral couple (deities), Efrikodsu and Dekpadsu. The couples, which others refer to as witchdoctors Efriko and Nayo stayed at an area in the west known as Dibenkpan (Dibengpa), which is situated close to Dikpéléou in the south-east (Debrunner 1968:553; Cornevin 1969:45). Ergo, the Adele points to Dibenkpan (Dibengpa) as their ancestral home.

Cornevin (1969:45-46) contends that various Bédéré (Adele) clans oral tradition support the claim that they came from the west and passed through a place called Dikpéléou, where Nayo’s witch doctor resides, great divinity of the Eastern Adele, honored by a few hundred meters south of the village on a height called Dipongo. It is said that all the Bédéré (Adele) groups passed through Dikpéléou, primarily for religious reasons and also because it is the access route the most convenient for climbing the cliff (Cornevin 1969:46).

One oral tradition asserts that when the Adele came out of Dipongo height to the open land, they found the land empty, hence they see themselves as the owners of the land, whilst another version cited by Heine (1968) contends that the Adele met “autochthonous” inhabitants and absorbed them when occupying their new territory. “During this spread, the Adele encountered a population that was familiar with iron production. This is likely to have been the autochthonous inhabitants of this area, who from the immigrants from the south were absorbed “(Heine 1968: 32). Kleinewillinghofer (2000) argues that these autochthones met by the Adele were either related to or were the forefathers of Cala (Kabye, Kusuntu, and Tem) and Dulo (Ntrugbu) who were then not separated. This flows from the fact that Adele requested to start a settlement on the southern part of the Cala territory, sometime in the 18th century, possibly after the fatal raid of the Ashanti.

The ancestors of the Bédéré (Adele) created their first villages of Yégué and Ketchenké before moving on to establish Odomi. Afterward, the people founded towns such as TendJouro, Toumouroumou, Koui, Ossingui, and Kalabo. Later, some people detached themselves from Ketchenké under the supervision of an Adjouti from Shiaré called Assouma. This Assouma went on to found Assouma Kedeme. M’Poti was said to have been founded by a foreigner (probably Dagomba). The village of Nkonkoa was developed by two hunters, Lalamila and Nkengbé.

Reference

Brindle, Jonathan, Mary Esther Kropp Dakubu, and Obadele Kambon. “Kiliji, An

Unrecorded Spiritual Language of Eastern Ghana.” Journal of West African

Languages 42, no. 1 (2015): 65-88.

Cornevin, Robert. (3 édition). Histoire du Togo. (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1969).

Debrunner, Hans W. “Gottheit und Urmensch bei den Togo-Restvölkern.” Anthropos

- 3./4 (1968): 549-560.

Heine, Bernd. Die Verbreitung und Gliederung der Togorestsprachen. Vol. 1. (D.

Reimer, 1968).

Kanchoa, Laré. “La Classification Nominale du Gidere, Langue Volta-Mono du

Togo et du Ghana.” Littérature, Langues et Linguistique (2014).

Kleiner, R. “Points of Contact between Adele Beliefs and Christian Beliefs.” Research

Review 14 (2000): 173-179.

Kleinewillinghofer, U. “The Noun Classification of Cala (Bogoŋ) – A Case of Contact-

Induced Change.” Nominal classification in African languages. FAB 12 (2000):

37-68.)

Ntewusu, Samuel, Richard Awubomu, Diana Amoni Ntewusu, and Grace Adasi.

“The “Okule” Cult Education and Practice in Ghana.” Journal of Interdisciplinary

Studies in Education 9 (2020): 114-133.