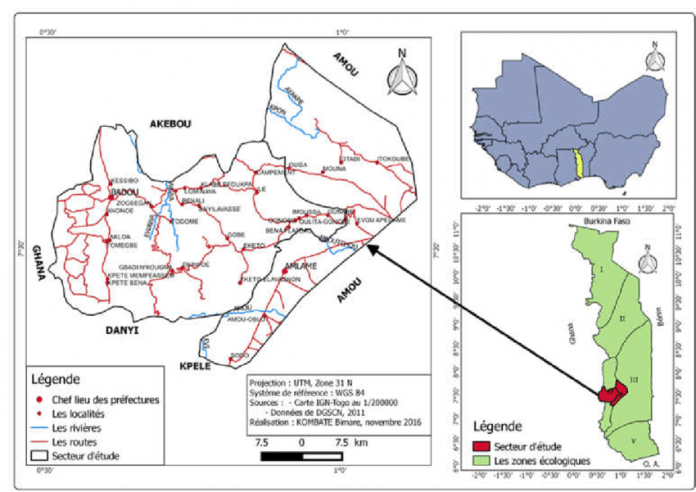

The Akposso/Kposso (Akpɔssɔ/Kpɔssɔ) are Guan, agriculturalist Ikposo-speaking people residing in the Plateau Region of southern Togo, west of Atakpamé, and across the border in Ghana. In Ghana, the Akposso lives in various towns in Jasikan, Biakoye, and Kadjebi Districts in the Oti Region. One of their famous towns is Apesokubi in the Biakoye District. In Togo, the Akposso lives in the Wawa and Amou Prefectures in the Plateau Region. Some of the towns include Amlame, Oblou-Amou, Atakpamé, Ahepe Akposso (Ahepeakposso), Badou, and others. There are more Akposso in Togo than in Ghana. The Akposso land is a space for Ewe and Ga-Dangme groups. Gayibor & Kossi-Titrikou (1999) contend that within Akposso land are Bassè-Dangme group who the turbulences of history have dispersed into Togo and Ghana, but had developed specific strategies to create a living space and manage it without jeopardising group cohesion. Hence, these Bassè-Dangme group is assimilated into Akposso.

The Akposso calls themselves and their land as Akpɔssɔ/Kpɔssɔ and their language as Akpɔsɔ or Ikpɔsɔ (Ikposo). Akpɔssɔ/Ikpɔsɔ is a member of the Ghana-Togo Mountain languages (GTM), formerly called Togorestsprachen (Togo Remnant Languages) or Central Togo languages (Dakubu and Ford 1998). GTM is composed of fourteen languages including Animere, Kebu, Tuwuli, Igo, Siwu (Akpafu and Lolobi), Nyagbo (Tutrugbu), Likpe (Sɛkpɛle), Lelemi, and Avatime (Siya) amongst others that are spoken on the mountains of Ghana-Togo borderland. These languages form a subset of the Kwa subgroup of the Volta-Comoe branch of the Nige- Congo language family. Anderson (1999:186) contends that unlike most Kwa languages with a five-height cross-height vowel harmony system, Ikpɔsɔ has ten contrastive vowels and not nine.

Ikpɔsɔ has two dialects: Northern Akposso (Akposso Atadi) and Southern Akposso (Akposso Sodo). However, the name of the two major dialects spoken in Ghana and Togo are Iwi (Uwi) and Litimé (Afola-Amey 1995; Anderson 1999). The Uwi dialect is spoken mostly on the Akposso Plateau. Ikpɔsɔ is related to Ahlo (lgo), spoken in Togo, and Bowili (Tuwili), spoken in Ghana. Because the Ewe and the Bassè-Dangme (who are assimilated to the Akposso) live on the Akposso land, the Akposso are trilingual (Akposso, Ewe, and Dangmé dialect), which allows them a better penetration of the surrounding groups.

The ethnonym Akpɔssɔ (Akposso), according to Cornevin (1969:44), means égaux aux panthètes “equal to Panthers.” This makes the Akposso are people with bravery, strength, and fortitude equal to that of panthers. They were a warrior group known for their belief in Traditional African Religious systems. Hence, they have community, family, and individual deities. They also propitiate the earth, and the outi-ola “priest of the earth” is responsible for repairing the wrong done (libations) and excommunicating the guilty. The Akposso believe that their ancestors emerged from the ground with the help of their guardian deity, Obuo Wiletu. As a result, the place where the ancestors came to earth is therefore given religious significance. The Akposso have a traditional calendar that has five days each week. These are Imle, Ekpe, Ewle, Eyla, and Eva.

The Akposso are well-known farmers. The physical conditions of their land are relatively favourable for arboriculture, hence the area is noted for production and commercialisation of fruits grown together with cash crops such as cocoa and coffee since their introduction into the region in the early 20th century (Abotchi 2006). They also cultivate traditional crops such as yam, Cassava, Cocoyam, taro, rice, ɖzukklɔ “maize/corn”, and ɔva “fonio”. Because the fonio played a significant role in the battles against their enemies, the Akposso alongside the Akebu celebrate an annual festival called Ɔvazu/ Ovazu “Fonio Festival.” The Ovazu is celebrated every 2nd Saturday of December alternatively in Amlamé and Badou.

In the past, Akposso like all other Guan groups was a non-centralised society with a dynamic lineage and segmentation system. Each of the Akposso villages constitutes an autonomous and independent socio-political entity, despite state or ecclesiastical administrations (Kossi 1998). It was a society without a leader, with gerontocratic leadership. At the head of each oudounou “the big house” was an evlé “the oldest group.” The oudounou only exercises power over his group. Everyone does what he wants with few rich men and priests holdings power in this society of “an ordered anarchy.” Bassa (2006) explains that relations between lineage or territorial groups adhere to codified rules with priests attached to deities and patriarchs (senior member of a lineage) of an olouka “institutionalised council” the individuals with authority in ensuring obeisance to the law and the management of public affairs. Even though a patriarch of an olouka is a coordinator and primus inter pares, his power was more conciliatory than coercive. Bassa (2006), further explains: ”On the other hand, as the exclusive holder of the cult of ancestors celebrated through the ancestral stool, he enjoys significant religious prerogatives. His seniority makes him an essential intermediary between the world of the living and that of divinities and ancestors. As such, its preeminent role in the creation of new cities is recognized. After the priest attached to the protective deities has located a site, he proceeds to the consecration of the place (libations) before the rest of the group joins him. In the event of a violent split within the group (family conflicts), the new installation is transformed into a new origin and gives rise to the production of strongly pictorial stories…”

The idea of chiefship in Akposso society was a colonial creation brought to the people by the Germans. The chiefship was started when the Germans reached the Akposso village of Bato on 27 April 1888 and later signed a treaty with Wampah de Bato, the powerful Headman of Bato who has used brute force in the area to put fifteen villages under his authority. As a result of Wampah’s power in the area, the Germans described him as hauptmann “captain” or “chief” and was conferred with the honour of Hauptmannde Bato on 13 January 1889 (Ali-Napo, 1980: 61). When the Germans founded the Bismarckburg, Wampah became a cooperative chief of the Germans in the area and not the superior chief of the Akposso. The first superior chief of the Akposso was Mawoussi of Tchakpali who reigned from 1890 to 1896 (Bassa 2006).

Origin and Migration

The Akposso have various theories of origins. One theory asserts that they and their neighbours, the Akebu believe that “God put them on the mountains” via their various ancestors (Debrunner 1968:552). The Akposso argue that their first apical ancestor called Oboè or Tchokolobi came from the bowels of the earth on the Kossa Mountain Cave, which is in the northeast of the Ghanaian Akposso town of Akposso-Koubi (Apesokubi). It is said that Oboè had the assistance and cooperation of a protective and guardian spirit, Obuo Wiletu that emerged from the Kossa Cave. The deity revealed all the secret ritual performances and taboos on how to worship him to Oboè. Thus, he became the first priest of Obuo Wiletu, and it also explains why when the most important ceremonies associated with rice cultivation is performed at the Kossa Cave three times a year to their guardian spirit, Oboë’s name is mentioned in the libation prayers as the first priest of Obuo Wiletu (Debrunner 1968:557). Akposso claims that Oboë married later and had seven children who founded the original seven villages of Témé, Gbohou, Tadi, Nahoua, Ouakpa, Tchakpali, and Evou on the Kossa Plateau. It was from these seven villages that the Akposso moved out to establish various towns and villages such as the city of Akposso-Koubi (Apesokubi), which is now stated to be in modern Ghana.

The second theory collected by Bassa (1996) asserts that the ancestor of the Akposso called Ida, ‘emerged from the ground’ {a commonly held basis for allodial rights} close to a mountain in Gbohoulé, a place located about ten kilometres south-east from Tététou in the Moyen Mono district in Togo”. Ida is then reputed to have been translated magically to a place called Agbogboli, from where his numerous descendants moved to the uplands of Kossa, founding Akposso-Koubi (Apesokubi) in Ghana. The third theory continues from here that whilst living in Apesokubi, two sons of Oboè (Tchokolobi) moved out of the town to found their own villages. Isso, the first son of Tchokolobi founded Issoto on the mountain and proceeded to Kpélé (Kpolo) and Agbogbome before coming back to die at Loboto, where the Akposso communities of the Plateau (Témé, Gbohou, Tadi, Nahoua, Ouakpa, Tchakpali, and Evou) lie. The village of Edifiou, however, is the religious centre of the descendants of Isso and his direct descendants in the area were Nege, Igala, Otchou, Essi Adjakpa, Oklou Djéké, Bodié, Dotchéke, Olobi, Midié, Attigbé, Lhou chief and others.

Enouli, the brother and the second son of Tchokolobi also wandered past Bato, which shares a border with Kpessi to go and settle in Aféye, where he dies. Many of his descendants are found in the villages of Akposso Plateau and Akposso-North. It is said that on the Western cliff of Akposso Plateau, a band of warriors led by one Akposso warlord, called Yalou, attack the Akpafo, who lived in the current town of Litimé, and drove them southwest to the where they founded their towns of Akpafougan, Odomi, Mempeasem, Lolobi, lklé, Kpakebo, Ekoutsefo (Cornevin 1968:45). The Akposso were able to gain victory over their rivals because the steep mountains discourage potential pursuers, and they also used their young pretty girls to bargain for peace from their adversaries by marrying them to their chiefs.

Koevi (1970) and Kpodzro (2018), however, trace the ancestry of the Akposso to Egypt (Nubia) where they lived in a locality called Apanso. This locality was said to be a place of wealth but it was invaded and subjugated; reducing its inhabitants to mere slaves. This turn of an event forced the Akposso who refused to be dominated by the invaders to emigrate (Koevi 1970:10). The Akposso first wandered to Sudan and moved eastwards to settle at the loop of the Great River in the Niger valley. After staying peacefully in the Niger loop for some time, another group of warrior tribes emerged in the area and started attacking the Akposso who were known for their expertise in hunting (Koevi 1970:10). As a result of the attacks, the Akposso journeyed further southeast and entered the forest territories of Ghana.

The Akposso moved on and stayed in various places before reaching the region of Agbogbome, an area which their ancestors say was infested with ferocious beasts. This place was close to the mountain in Gbohoulé, near Mono (south of Sagada). From Gbohoulé, the Akposso travelled to the northeast to occupy an area close to the Mahi of Savalou, and then later made a u-turn to live in the kingdom of Notsie (Nuatja). At Notsie, Agokoli, the powerful tyrant of the Kingdom of Notsie maltreated the Akposso by always using them for human sacrifice and other rituals. This dastardly acts towards that Akposso forced them to flee the area and crossed the mountain to the west to occupy the Ahlo enclaves. Cornevin (1969:44) contends that it was whilst the Akposso were living on the Ahlo enclaves that the Asante in their Ewe Campaign fought the Akposso and were defeated. It is said that when the Asante were defeated on the Plateau, they fled and started shouting: Akposso eku bi/Akposso koubio “the Akposso has killed us.” This brought the name of the town Akposso-Koubi or Apesokubi in Ghana (Cornevin 1969:44).

Reference

Abotchi, T. “La Production et la Commercialisation des Fruits en pays Akposso au

Sud-Ouest du Togo.” Journal de la Recherche Scientifique de l’Université de

Lomé 8, no. 1 (2006).

Bassa, Komla-Obuibé. “Contribution to the History of Akposso: “the Logbo.” (M.A.

Thesis, Department of History, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, University

of Lomé, 1996).

___.”Genesis and Transformation of a Colonial Political Institution. The Yovofia

among the Akposso, Bèdrè and Ekpèbè of Togo.” Journal of Anthropologists.

French Association of Anthropologists 104-105 (2006): 109-128.

___.”Histoire et migration des Akposso du Sud-Ouest des Monts Togo.”

Cornevin, Robert. Histoire du Togo. (Paris: Editions Berger-Levrault, 1969).

Dakubu, Mary Esther Kropp, and Kevin C. Ford. “The Central-Togo Languages”, in:

Mary Esther Kropp Dakubu (ed.), The Languages of Ghana. (London/New York:

Kegan Paul International for the International African Institute/Methuen, 1988).

Debrunner, Hans W. “Gottheit und Urmensch bei den Togo-Restvölkern.” Anthropos

- 3./4 (1968): 549-560.

Gayibor, Nicoué, and Komi Kossi-Titrikou. “Stratégies Lignagères et Occupation de

l’espace: Le cas des Adangbé émigrés au pays Akposso au Togo.” Outre-Mers.

Revue d’ Histoire 86, no. 324 (1999): 203-228.

Kossi, Ankou. “Association de Ressortissants au Togo: Enjeux de Développement,

Enjeux Socio-Culturels et Politiques: Etude de cas dans le Groupe Ethnique

Akposso.” (PhD Dissertation, Paris, EHESS, 1998).

Kpodzro, Yaovi Fadzi. Opuscule de l’histoire des Peuples Akposso: Origine, Mythe

ou Réalité. (Paris: Agence francophone pour la numérotation internationale du

livre (AFNIL), 2018).