Introduction

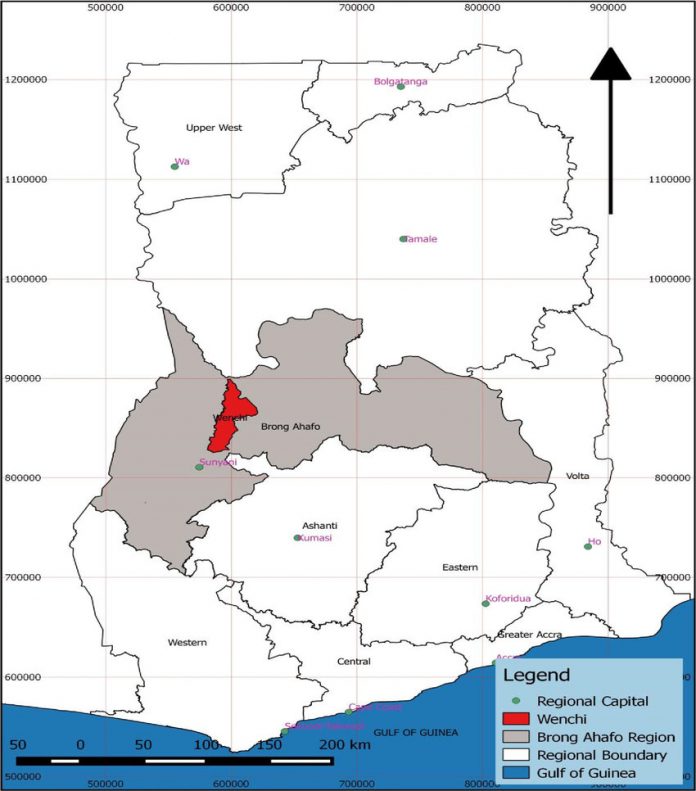

Wenchi (Wankyeɛ/Wankyie) are agroforestry sub-Bono Twi-speaking people that form part of the Bono ethnic group that belonged to the larger Akan ethnolinguistic group in Ghana and Ivory Coast. Wenchi is Bono people and their town/state is also called Wenchi. Wenchi state the capital of the Bono Municipality of the Bono Region in the middle-belt of Ghana. The Wenchi Municipal Assembly was one of the two local authorities created in 1974 to oversee the then Nkoranza, Techiman, Yeji, Attebubu and Kintampo in the Brong Ahafo region. The Decentralization reforms of 1988 established it as a district by Legislative Instrument 1471 of 1989. In 2004, with the creation of Tain District, the Assembly operated under Legislative Instrument 1782 of 2004. The district was later upgraded to a municipality status by Legislative Instrument 1876 of 2007.

The Wenchi are noted for their farming activities and intellectual prowess amongst the Bono. It has people from various ethnic groups living in the town and its neigbouring villages. Hence, Professor Kofi Abrefa Busia, the worthy son of Wenchi asserted that Wenchi is a cosmopolitan town and has a beneficial symbiotic relationship with its majority stranger population (Busia, 1968: 147-148; Baku, 2006:452).

Historically, Wenchi was one of the earliest independent states but it was made part of the Ashanti territory during the British colonial administration. This flows from the fact that Wenchi was subjected to Asante imperialism in pre-colonial times. It, however, became part of the Brong Ahafo Region which was created on 4 April 1959 by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention Peoples Party (CPP) regime of Ghana’s first republic. Currently, it is part of the newly created Bono Region. Wenchi shares boundaries to the southeast with a historical cradle of Akan civilization, Bono Manso (Techiman), and the ancient trading centre of Begho. It was first shown on one of the earliest Dutch maps of the states of the Gold Coast in 1629 (Boahen, 1975: 8). The Dutch maps described Wenchi and recorded it as possessing ‘beautiful cloths and gold with trade with the Acanists’ (Mustapha and Goody, 1965:156).

The name Wenchi is an Anglicisation of the Akan-Bono zoonymic name Wankyeɛ/Wankyie, which means “Steppe Pig.” Wankyie, indeed, is an animal of the steppe-like a pig and it burrows the earth. This underpins Donkor (1972: 8) postulations that Wankyie means “the abode of pig-like animals”. The appellation of Wenchi is Wankyeɛ atete kroman, daammere pintinpi, patampa abo bon ma pranyini anya baabi ada. Kɔtɔkɔ si aguo a, na oboɔ damu “Wenchi the ancient state, where the steppe pig whose titles are ‘the irrepressible, the impregnable’ made a burrow for the giant armadillo/great elders to have a place of residence. When the Porcupines ‘Asantes’ would do anything and the Wenchi are present they quit.”

Origin and Migration

There are two competing traditions of origins of Wenchi which underpins the contest of the Wenchi Stool by Ahenfie Yefri and Safoase Yefri families (Ameyaw, 1965; Busia, 1968; Baku, 2006). The Ahenfie Yefri oral tradition asserts that their apical ancestor, Nana Asaseba Odensie or Asase Yaa Baodensie came out of a hole in the ground at Asomanini, a place near the source of the river Ayansu/Ayesu nine miles south-west of Wenchi. This hole is the site for the festival known as Murukuo. It is said that Nana Odinsie, the elderly woman emerged from the ground with his six children: Nana Hemaa Toa I, Nana Hene Doo/Doon, Nana Adwoa Bowi Ansa, Nana Anye Amoampong, and Nana Anto (Ameyaw, 1965: 1; Baku, 2006: 453). Odensie also came with two gold-bearded stools called Ahwene Kokoo “red beads” or Ahwene dwa “beads stool” which were male and female stools, thus making Nana Odinsie both the King and the Queen mother.

Tradition further asserts that Nana Odensie was to come with chief but this unnamed chief who was to bring the rear from the hole could not come because one Nkrumah had come out of the hole which was dark and had seen the light shouted. As a result, the chief who was about to come withdrew into the hole. Nkrumah was killed over this sacrilegious act. This led to the early Wenchi tradition of killing their ninth-born child ‘Nkrumah’ but allowing the tenth-born child, Badu” to live (Ameyaw, 1965). The surviving descendants of Nkrumah are the members of Afua Mankoto house, the occupant of the Atonfoso or the Werempe stool. It is said, that light was taboo to the indigenous Wenchi people when they lived in the hole. Because of the breach of this taboo, the early settlers named the town they built as WANKYI/WANKYEƐ (Ameyaw 1965). Before their being called Wankyi/Wenchi, the people were first called Yɛfiri ‘we came out of the ground’.

The Sofoase Yefri oral tradition on Wenchi claim that their ancestress, Nana Asase Yaa Ba Odinsie emerged from a hole when Wankyeɛ, an animal of the steppe-like a pig burrowed a hole from which came numerous people, followed by their ancestral stool for the chief. The chiefs climbed on the golden ladder to emerge from the burrow. The chief brought the rear but recollected that the stool- carriers had left behind in the hole, the Kanta ‘an iron plate’ on which the stool rested. When the stool carrier descended into the hole to collect the Kanta, a hunter on an expedition nearby who saw the host of people who have emerged from the hole started shouting. This made the animal ‘Wankyeɛ’ escape and the burrow filled up. Immediately, the people pulled out the golden ladder by which the members of the royal lineage had climbed. This golden ladder is now a relic of the descendants of Nana Asaseba Odensie. The Commoners climbed up by a chain.

Sofoase Yefri, the ruling house to which Professor Kofi Abrefa Busia belonged, maintained that Odensie emerged from the whole with two infant children: a young son named Nana Aniampong Tabrako and a young daughter, Nana Afua Atoa together with male and female stools. Nana Tabrako inherited his mother’s male stool to become the king whilst Nana Afua Atoa inherited her mother’s female stool and became the Queen-mother. Nana Atoa was said to have six children: Nana Adoma, Nana Anye Amoampong, Nana Doo, Nana Ani Anto Ahensan, Nana Kwabena Tanoand Nana Kofi Djan (Baku, 2006:456). These children inherited the male and female stools of their mother and uncle, Tabraku.

Sofoase Yefri discounts Ahenfie Yefri claims of origin and moves further to asserts that Ahenfie Yefri group were strangers from Kojokrom in Ivory Coast who came to Wenchi during the reign of Nana Frema I, who was then reigning as the Queen-mother of Wenchi. Nana Frema welcomed them and integrated them into the male and female stool houses of Wenchi. These were to help beef up the membership of the Wenchi royal household and also enabled Nana Frema to secure men to help Asante in their Anlo Campaign as an ally of the Asantehene (Busia 1968:17; Baku, 2006:457). As a result, the Ahenfie Yefri was originally referred to in Wenchi as Nkruwasefo or Yefri Ntwetosuo “persons drawn in to ‘fill the gap in the Sofoase family at an emergency time’” (Baku, 2006:457).

There is a third theory on the origin of Wenchi that is also linked emergence of Wenchi to Nana Asaseba Yaa Odinsie. These people who claimed to be original Wenchi people are known as Nkwaduano Yefri or Nkwaduasefo. Busia (1968:3-4) contended that Nkwaduasefo and Sofoase Yefri are the indigenous or original settlers of Wenchi for which reason they are referred to as Yefrefo.

Moving away from the two major competing traditions of origin and the non-competing third case, the Wenchi after emerging from the ground stayed at Bonsa ‘valley’, a little off the hole they emerged from. They moved on to found Ahwene Kokoo where they were they came into contact with the Asante aggression and expansionism under their powerful King, Ɔpemsoɔ Osei Tutu I. Osei Tutu who has heard of the gold-bearded stools attacked Wenchi but the Wenchi protected their stools by burying them on the bed of Tain River. In anger, the Asante destroyed Ahwene town, their Queen mother-King, Nana Toa Dankoto who was washing in the River Tano was captured and sent Kumase (Ozanne, 1968; Daaku, 1968; Boachie-Ansah, 1975). This led to the scattering of the people of Wenchi, with some moving to the present-day Ashanti, Bono, and Western Regions of Ghana (Mustapha and Goody, 1965:160).

Nana Toa Dankoto’s arrival in Kumase was said to have occasioned a severe rainstorm that struck Kumase and violently shook the Manhyia Palace of the Asantehene. The nyedua “shade tree” in the palace was hit by thunder. King Osei Tutu upon inquiring from the priests was told the calamity from the rainstorm was a result of his continuous incarceration of Ohemaa Toa who is a daughter of the Tano River deity. As a result, King Osei Tutu released Ohemaa Toa Dankoto, who earned the appellation, Nana Toa Sramangyedua “Grand matriarch Toa, the thunder that strikes the shade tree.” It must be noted that whilst Nana Toa as the eldest daughter succeeded Nana Odensie’s female stool as Queen mother, Nana Hene Doo who was the eldest son of nana Odensie later succeeded her male throne as the first King/Chief of Wenchi.

Festival

The major festivals celebrated in the Municipality are the Apoɔ (Apour) and Yam festivals. The annual Apour festival is celebrated between April and May. The major significance is that it gives the citizenry the right to come out openly and criticise those in authority. It also serves as a period for introspection for those in authority to re-assess them and make amends for any wrongdoings, to promote effective development. The yam festival is also celebrated between August and September, annually to mark the two farming seasons. It serves as an occasion for thanksgiving to the gods of the land and the ancestral spirits for a bumper harvest and protection during the season. This helps maintain the relationship between the ancestral spirits and the living.

Reference

Ameyaw, Kwabena. “Tradition of Wenchi (Wankyi), Brong Ahafo”, in: Kwabena

Ameyaw (ed.),Oral Traditions from Brong Ahafo. (Accra: Institute of African

Studies, IAS, 1965).

Baku, Kofi. “Contesting and Appropriating the Local Terrain: Chieftaincy and

National Politics in Wenchi, Ghana”, in: Irene K. Odotei and Albert K.

Awedoba (eds.), Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, Governance, and Development.

(Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers, 2006).

Boachie-Ansah, J. “Ahwene Kɔkɔɔ: A Seventeenth-Century Wenchi Capital?.”

Sankofa 1 (1975): 85.

Boahen, Albert Adu. Ghana: Evolution and Change in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. (London: Longmans, 1975).

Busia, Kofi Abrefa. The Position of Chief in the Modern Political System of Ashanti. (London: Frank Cass, 1968).

Daaku, Kwame Yeboa. “A Note on the Fall of Ahwene Koko and its Significance in

Asante History.” Ghana Notes and Queries 10 (1968): 40-44.

Donkor, Charles E. Nkrumah and Busia of Ghana. (Accra: New Times Corporation,

1972).

Mustapha, T. M., and Goody, Jack. “Wenchi and Its Inhabitants.” Research Review

- (1965):

Ozanne, Paul. “Ahwene Koko: Seventeenth-Century Wenchi.” Ghana Notes and

Queries 8 (1966): 18.