Introduction

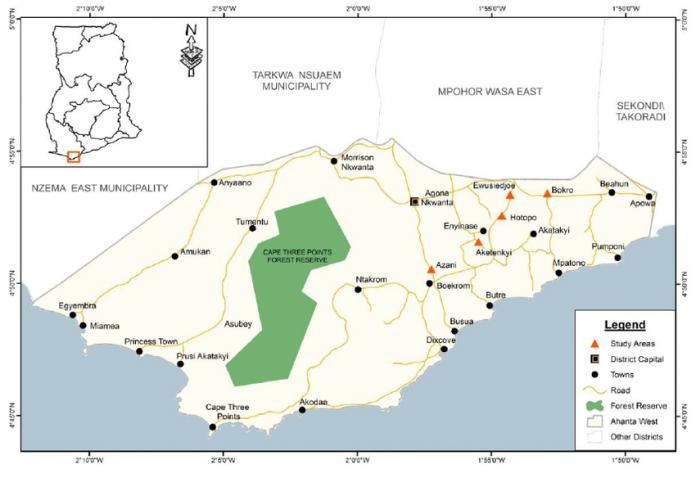

The Ahanta are aboriginal fishery and agro-forestry Akan Bia and Mfantse speaking people living in the Western Region of Ghana. Ahanta had dual ancient Guan and Akan heritage with their ancestry traced to Asebu-Amanfi’s Asebu group and the Akan-Bono. However, as a result of their interaction with the Bɔrbɔr Mfantse, the Ahanta speaks both Bia-Ahanta and Mfantse languages. Linguistically, Anquanda (2013) contended that Ahanta resembles Baoule, Sefwi, and Nzima. This makes them bilingual Akan people as a result of the socio-cultural and political interaction. The Ahanta land spans from Beposo to Ankobra in what is now the Western Region of the Republic of Ghana, a regional power in the form of a confederacy of chiefdoms that had come in early contact with the European nations settling on the Gold Coast for trade. The Ahanta land has been historically known as one of the richest areas on the coast of Ghana. Ahanta people migrated from their settlement to the Oti enclave to become the people of Avatime (Brydon 1976). Thus, Avatime is a descendant of the Ahanta. Some of the Ahanta towns are Busua, Dixcove, Butre, Princes Town, Aketakyi. Egyambra, Sekondi, and others.

The name Ahanta means “the one who stands to dry his wet body.” It emerged from the expression nkorɔfo yi w`anhanta hɔn ho ‘this people did not dry themselves’. This expression was shortened to Ahantafo “People who had not dried themselves” or “the one warm himself/herself after being wet or cold.” The appellation of Ahanta State is Kɔkɔtɔ wokyiri me, Kɔtɔkɔ wokyiri me; Ntɛtɛ ne odupo ne gyapɛn ɛfi tete tete tete. Etwa gu, Etwa gu “Porcupine you hate me, Porcupine you hate me; Ants and mighty tree and ogyapam are from long, long, long time. Cut down! Cut down!”

Historically, Ahanta was one of the earliest Gold Coast coastal towns to receive Europeans. As a result, the Dutch built their first edifice on the Ahantaland, Fort Orange at Sekondi in 1642 and the second one, Fort Batenstein at Butre in 1656. After successfully driving the Portuguese away in 1717, the Dutch gained control over the trade, particularly in Ahanta areas. Ahanta became the main trading grounds for the Dutch on Gold Coast. On 27th August 1656, the Butre treaty was signed between the Ahanta chiefs and the Dutch which made Ahanta a protectorate of the Dutch from the attacks of other European nations who had an interest in the ongoing slave trade. A pact that lasted for 213 years until 1871 when the Dutch left the Gold Coast and the British took over. It was the longest pact between a European nation and an African state. This pact became the basis for the annihilation and desolation of Ahanta as expedient forces marshalled by the Dutch marched on Ahanta on 30th June 1838 led by Major-General Jan Verveer from the Royal Netherlands Army. Major Ahanta towns like Takoradi and Busua were massacred and a large military presence was maintained in Ahanta. Asantehene alone offered 30,000 troops though the Dutch turned down his offer and believed it to be a ploy for the Ashantis to gain direct trading access with the Europeans at the coast.

In the course of war Badu Bonso II was captured and on 27 July 1838, he was hanged after which his head was removed and sent to the Netherlands where it got lost for more than a century until it was rediscovered at Leiden University Medical Centre by one Arthur Japin who was conducting research and had earlier on read about this great Ahanta king who stood against foreign invasion and interferences. The head had been stored in a jar of formaldehyde for about 170 years. In 2009, after a brief ceremony was conducted in Hague, the head was returned to Ghana previously known as the Gold Coast where it was originally taken away by the Dutch.

In 1871, the Dutch sold all their trade possessions to the British who have already built Fort Metal Cross at Dixcove in 1683 and were very active in the ongoing slave trade and left the Gold Coast after they have robbed Ahanta of everything including her pride and dignity. The British took over from the Dutch until 1957 when Gold Coast became independent and by then there was nothing left that Ahanta can boast of. From 1471 to 1957, Ahanta and other coastal Akan states were constantly oppressed and suppressed by several European nations particularly the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British. In it all, foreign influence on Ahanta and other coastal Akan states lasted for 486 years. A period long enough to destroy everything Ahanta. Once a beautiful Ahanta kingdom was left disorganised to date.

Origin and Migration

The Ahanta and the Asebu were people known as Sabou. They were said to be part of the migration from the upper Nile under the leadership of the legendary Asebu Amanfi, the founder of Asebu State. The people left their original settlement as a result of war and migrated to Lake Chad where they lived by the side of a river called Sabou. It is believed that it is from this river the state derived its name ‘Asebu’, meaning “countless warriors” (Allou 2008:184; Foot & Jones, 1903:21). The Asebu moved southwards to the Bini (Benin) region at a time ‘when the tribes there were fighting each other.’ Meyerowitz (1974:85), however, contended that in avoiding the conflicts in the area, Asebu moved on to finally settle at the southeast of Benin City in a country (which is still named after them, -Sabou/Sobo). Thus, Sabou was in Benin, and not in the Lake Chad enclave.

Asebu lived peacefully in the Benin area for several years until ‘the arrival of a people whose men wore thirty-two marks on their faces and their women sixteen” (Meyerowitz 1974: 85). These ruthless warrior groups forced Asebu to move to the Ile Ife region, which is in the north of Benin City. They continued their journey by moving to the coast to find uninhabited land to settle in. They constructed boats from ’light pieces of flat wood’, or made out of ‘large calabash’. The women, the potter, the carriers of their sacred stone figures, and the blacksmiths, to whom the sea was taboo, walked along the beach (Meyerowitz 1974: 85).

Hence, by the flat wood/calabash sea boats and trekking on the shores from Benin, the Asebu finally stopped at Brofobepɔw (European Hill/Brow of Promontory) on the Moree beach (Opoku 1969:82). It was this spectacle that an eyewitness described the Asebu and Ahanta as people that emerged from the sea on the backs of whales. It is said that the multitudinous crowd was led from the sea by Asebu Amanfi the Giant, his two brothers: Nana Mbro and Ɔfarnyi Kwegya, and their sister Amanfiwa. The other faction were led by the patriarchs including Nana Tsikwadu, his elder brother Nana Badu Bonsu, and Aberewa Tsiawiem Efuwa (Opoku 1969:82). The movement from the sea and the shores to the land took five days because of the sheer number of their population. Their number was only cut short when a certain hunter who saw this spectacle clapped his hand and exclaimed, wɔ dɔɔso papa ‘how numerous!’ (Reindorf 1895:268; Sanders 1980). These words caused the line of people coming from the sea to suddenly cease. The people upon moving upland built their first settlement, Asekyere Bedzi close to Brofobepɔw (Meyerowitz 1974:85).

Opoku (1960:83) recorded that when after arriving on the shore, Tsikwadu’s people said that they were wet and feeling cold, ntsi wobegyina mpoano ahata hɔn ho i.e., “so they will stand on the shore to dry their bodies. Thus, they became Ahanta “the one who stands to dry his wet body.” Crayner (2016), however, contends that it was whilst Tsikwadu’s group were standing in the sun with their wet bodies that the aboriginal Etsi occupying the land said nkorɔfo yi w`anhanta hɔn ho ‘these people did not dry themselves’. This expression was shortened to Ahantafo “People who had not dried themselves” or “The one who had now warm himself after being wet.”

After drying themselves at Asekyere Bedzi on Brofobepɔw “Whiteman’s Hill”, Opoku (1969:83) posited further that Tsikwadu with his elder brother Badu Bonsu and Aberewa Tsiawiem took the westwards trajectory to Edena (Elmina) beach which had developed out of Eguafo Kingdom. Asebu the Giant, his brothers, sister, and entourage climbed Dadze Koko ‘Iron Hill’ and descended to the base of Aberewanfo Koko ‘Old lady does not climb Hill.’ Here, Kwegya subjected the Etsi who were already living at the fishing village of Asekyere Bedzi on the Brow of Promontory or Moree after a fierce battle. Asebu the Giant and his favourite sister took the Akotekua/Akatakyiwa routes to settle at Fonfompɔwmu “the silent grove”. It was the place where the Asebu buried their dead after their war with the Etsi. From here, they moved to the interior to found Asebu state

For the Ahanta, because, Badu Bonsu was the elder brother of Tsikwadu, he (Badu Bonsu) became the leader and their first Chief. The Ahanta interacted with the chief of Elmina at the River Aborɔbe ano ‘Pinneaple Mouth,’ and the area became the boundary between them. The Ahanta stayed there for some time before taking another long westward trek until they reached River Ankobra, where the Nzima was settled. Thus, River Ankobra served as the boundary between the Ahanta and the Nzema. From here, they moved into the hinterland close to the aboriginal Wassa land of King Enimil Kwao Benso. The land they settled on was where the Anua River and a rivulet called Anu abɔe ‘Anu`s confluence’ lie. These two riverine bodies became the boundary between the Ahanta and Wassa.

After establishing their boundaries with Wassa, the Ahanta moved backward to the middle of their land to dig a big well know they have developed with dug-well, and since Badu Bonsu had become their leader, the place was called Bonsu Burɔso “Top of Bonsu’s dug-out well.” Nana Tsikwadu and his brother Badu Bonsu and the rest of the people settled there. It was whilst they were here that Nana Hima Dekyi and his people who had moved from the Bono enclave also came to meet them and was given land to settle. Unfortunately, the land that Nana Badu Bonsu gave to Nana Hima Dekyi and his people had no drinking water source, so they scouted on the land, moving from one place to the other. They one day, out of blues they came across a river. In shock, they said: eyi de efu yen mu “This has surprised us.” The expression was shortened to Mfuma, which is now the town of Dixcove (Mfuma). Thus Mfuma became the settlement of Nana Hima Dekyi’s Ahanta group. Mfuma’s name became Dixcove because a European Trader called Dick stayed on the hills of Mfuma, hence the name Dixcove.

It is said that an epidemic occurred amongst the settlers of Bonsu Burasu so they moved from there to build another settlement called Owurusuam “Let death come and take us from here.” The name Owurusuam was later corrupted to Busua, which is now the capital of Ahanta State with Nana Badu Bonsoe at their paramount Chief. Thus Mfuma-Busua became Lower Dixcove and Mfuma hills or Etsifi became Upper Dixcove with Nana Hima Dekyi as their Chief. On the founding of Sekondi, Opoku 1969:84) recorded that one Ɔwɔkunu or Ewu Eluku, a war captain of Nana Bonsu Esua Yankey Ansah at Bonsu Burasu left the settlement during the epidemic and moved on to found the town, Sekunde/Sekune (Sekondi). However, Maison (1974:5-7) Ewu Eluku, was a female leader of the Ahanta group left the Bonoland because of conflicts that affected the population of his male lines. Thus, whenever the issue of the men she lost in Bono conflicts is broached, Eluku answered: esa kum, ‘war has killed me’. Esa kum was vulgarised to Sekunde/Sekune (Maison, 1974:5-7).

Festival

The Ahanta people celebrate the Kundum festival. Kundum is a harvest festival and involves dancing, drumming, and feasting. It was in its original state a religious festival that was used to expel evil spirits from the town. Today, Kundum is celebrated as a way to preserve the culture of the Ahanta people and neighboring Nzema. The festival used to be one month long, but has been condensed to eight days. Relying on the oral tradition, late Kofi Agovi contended that:

Egya Kundu, the founder of Kundum festival, emigrated from Nzema and settled in the Ahanta village of Aboade. Shortly after his arrival, there was a great famine. An oracle was consulted which enjoined the whole society to imitate the drumming and dancing of some dwarfs who had earlier been discovered doing this by a farmer. The oracle’s prescription was followed, and the people’s hunger was brought to an end. Their natural reaction to the appearance of food once again was to give thanks for this unexpected benevolence. Dancing and drumming, originated by Egya Kundu, therefore became the means of expressing their sense of gratitude to their saviours. It can be seen in this brief account that a conflict-resolution mode, closely reflected in the related themes of « famine », « divination », « harvest » and « thanksgiving », forms the primary basis of drama in the Kundum Festival.

Refrence

Agovi, James Kofi E. “Kundum: Festival Drama among the Ahanta-Nzema of

South-West Ghana’.” (Ph. D. Dissertation, Institute of African Studies,

University of Ghana 1979).

___. “Of Actors, Performers and Audience in Traditional African Drama.”

Presence Africaine 116 (1980): 141-58.

Allou, K. R. “Histoire des Peuples et Civilisation Akan: Des Origines à 1874.”

(M.A Thesis, Universite de Cocody, Abidjan, 2000).

Anquandah, James. “The People of Ghana: Their Origins and Cultures.”

Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 15 (2013): 1-25.

Brydon, Lynne. “Status Ambiguity in Amedzofe Avatime: Women and Men

in a Changing Patrilineal Society.” (Ph. D Dissertation, University of

Cambridge, 1976).

Etikpah, Samuel Edukubile. “The Kundum festival in Ghana: Ritual interaction

with the nonhuman among the Akan.” Journal of Africana Religions 3, no.

4 (2015): 343-396.

Foot, Lionel R., and Jones, Thomas Freeman Edward. The Gold Coast and the

Fantis: A Complete Compendium for Miners, Traders and Students of Native

Life. (London: Gold Coast Globe Pub. Co., 1903).

Maison, Kojo. B. “The History of Sekondi.” (B.A., Dissertation, University of

Ghana, 1974).

Meyerowitz, Eva L. R. The Early History of the Akan States of Ghana. (London:

Red Candle Press, 1974).

Opoku, Andrews Amankwaa. Mpanyinsɛm. (Accra: Waterville Publishing House,

1969).

Reindorf, Christian Carl. History of the Gold Coast and Asante: Based on Traditions

And Historical Facts, Comprising a period of more than Three Centuries from

about 1500 to 1860. (Basel: The Author, 1895).